The declaration by the Fathers of the Second Council of Nicaea in AD 787 on the value of producing sacred images and art works is about to get a belated boost.

The London-based Benedictine monastery of Ealing Abbey is launching in 2024 the UK’s first iconography diploma course run by Catholics for the Catholic Church.

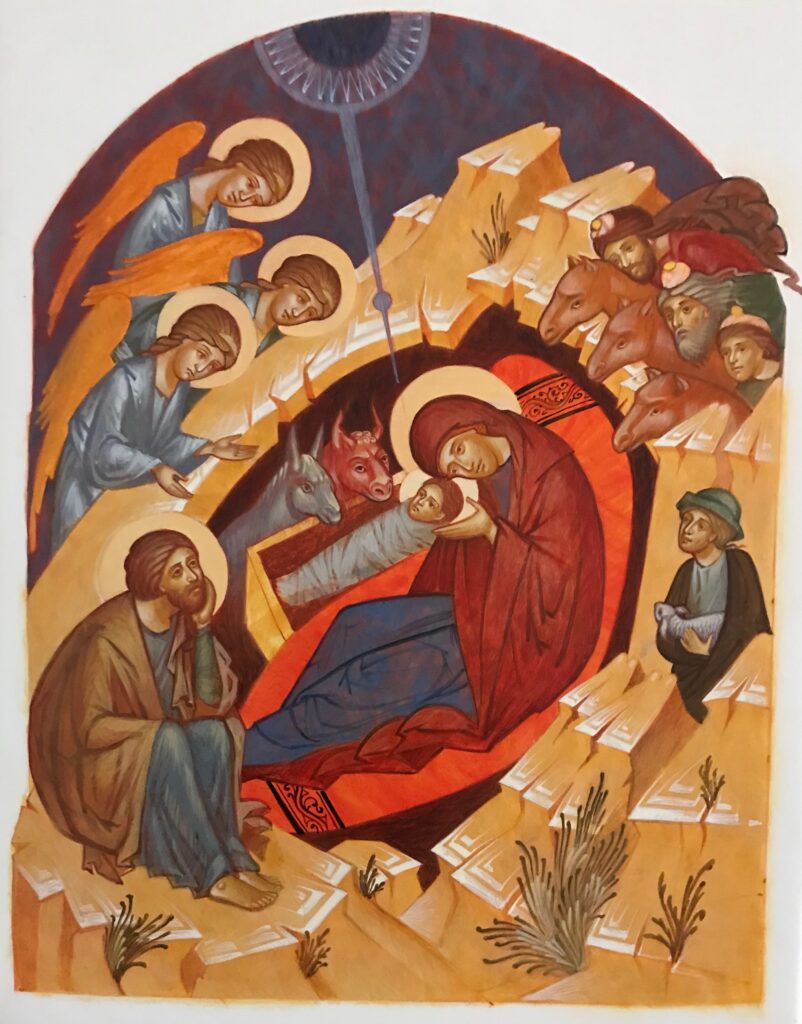

“Venerable and holy images, done in colour, mosaics and all other appropriate materials, of our Lord god and Saviour Jesus Christ as well as those of Mary Immaculate, the Holy Bearer of God, the honourable angels and all holy and pious people are to be exposed in the holy churches of God, on sacred vessels and vestments, on the walls and on the floors, in the houses and in the streets,” stated those Fathers of antiquity.

Fast forward to the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council, meeting almost 2,000 years after the Second Council of Nicaea, who directed bishops to “carefully remove from the house of God and from other sacred places those works of artists which are repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety, and which offend true religious sense either by depraved forms or by lack of artistic worth, mediocrity and pretence”.

They also decreed that “the practice of placing sacred images in churches is to be maintained” and that artists should “ever bear in mind that they are engaged in a kind of sacred imitation of God the creator, and are concerned with works destined to be used in Catholic worship, to edify the faithful, and to foster their piety and their religious formation”.

In addition, they called for “schools or academies of sacred art to be founded so that artists may be trained”—which is exactly where the new Ealing Abbey venture comes in.

Those behind the new course hope it will galvanise a Catholic art scene that in the UK has strayed from both the vision of the Fathers in AD 787 and those of the Second Vatican Council and, as a result, slipped into mediocrity and repetition. Authentically produced iconography, they argue, can serve to inspire and uplift the faithful, as well as potentially have a positive impact on contemporary challenges the Church faces, such as how to make the local church more attractive and inspiring to the faithful.

“Art is in crisis in the Catholic Church in this country,” says iconographer Amanda de Pulford, who is spearheading the course. “I see this as a cause as well as a symptom of the crisis of spiritual diminishment across our churches. We can do something about the situation. With leadership from our Bishops we can make a real difference.”

She is keen to point out that she is “not a new type of iconoclast”. She recognizes “that mass-produced, factory-moulded and identically coloured images from the nineteenth century are part of part of our heritage” and that “many have grown up with statues like this and use them for prayer and devotion”.

But, she says, “the faithful deserve to see more images in our churches which have been made by real artists [as] those are the images that can express the real experience of faith’. Of course, she acknowledges, the work should be very deeply rooted in tradition. “But faith is real and active and personal, so Christian artists cannot simply copy out precisely what was done before.”

The diploma will be delivered over four years, with each year divided into 2 terms covering a total of 32 weeks, and with 3 hours studio tuition at the abbey every Friday. For 2024, the pilot year, there will be a maximum of 15 students. Thanks to generous hosting by Ealing Abbey’s Benedictine Institute, the annual cost will be £1,140 per student. Dependent on sponsors coming forward, it’s hoped bursaries could be available later in 2024 for needy students.

The course has been described as “an answer to prayer”, by Fr Peter Burns OSB, who in October 2022 helped establish at the Benedictine Institute the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Dunstan Studio of Christian Art as a “first step in making a formal contribution to the visual arts at the service of the Catholic Church”.

Since then, the studio has cooperated with artists and projects—involving both religious and laity—across different religious denominations.

“This way of working is natural to monasticism,” says Fr. Peter, who is now the Christian Art Studio’s director. “The [studio] looks forward to promoting both theological thinking and artistic practise, especially in the service of the liturgical life of the Catholic Church.”

The new diploma course will be directed by de Pulford and affiliated to the ecumenical Brussels Academy of Icon Painting, which was established in 2005 by Irina Gobounova-Lomax, a renowned Russian iconographer.

“Though our students will learn to understand and use the language and conventions of classical iconography style, they will also be encouraged to discern how the influences of their life and times have informed their own development and aesthetic sensibilities,” says de Pulford, herself a graduate of the Brussels Academy.

“We aim to enable them to use that discernment to produce work that is true, authentic and contemporary as well as in continuity with the tradition of sacred art and the high standards associated with it.”

A key aim of the course—through combining sound technical teaching with exposure to relevant liturgy and theology—is to produce graduates who can design and not simply copy sacred images, de Pulford explains.

“This is the art that is needed, so that the believers of today, like the ones of yesterday, are helped in their prayer and in their faith,” she says. “It is sadly absent from too many of our churches.”

The unexpected challenges in getting the course off the ground has highlighted to de Pulford the sorts of problems faced by liturgical artists engaging with contemporary Catholicism in the UK.

“There seems to be precious little in place nationally to support contemporary liturgical artists,” de Pulford says. When she approached the Bishops’ Conference, she was told there was no bishop in place to champion sacred art – and no expert advisers to advise on the topic.

“The problem we are tackling is national,” points out de Pulford. “It needs a national champion.”

For the time being, de Pulford draws encouragement and inspiration from recent events in the iconography scene in Poland.

When de Pulford attended the Brussels Academy ten years ago she met a fellow student, a nun of the Monastic Communities of Jerusalem called Sister Mateusza Drewniak. After qualifying, the sister returned to Poland and set up an icon school in Warsaw affiliated to the Brussels Academy. The new school acted as a veritable mustard seed within Polish iconography teaching and has led to the creation of additional iconography schools.

“The growth of iconography [is] essentially a bottom-up movement, with the impetus coming primarily from the lay side, though with strong support in certain clergy circles, in particular more forward-thinking ones,” says Gobounova-Lomax. “We see what is happening as a natural development, that of people wanting to express their faith creatively, away perhaps from a certain traditional passivity, [and] experimenting with personal expressions of their Christian faith.”

Gobounova-Lomax

describes how “such creativity is fundamental in the way God has made

man, even if we have been at times slow to admit and encourage it”. As a

result, she says, “iconography, when practised properly, can be a

powerful tool for personal spiritual development.”

As a result,

she takes umbrage with how those of us in the UK tend to “consider the

icon as a purely Eastern specificity, with a certain exoticism attached.

This vision, propagated by the Russian post-1917 emigration, is is in

direct opposition to my teaching. A key point of my school and my vision

of the sacred image lies precisely its commonality to all the Church.”

She adds: “As to how icon painting will fare in the UK, once taught regularly and properly, it is difficult to

foretell. A major factor in both Poland and here in Belgium is the easy crossing of confessional

boundaries

between Catholic and Orthodox. A resurgence in icon painting, as I

said, can be a powerful tool for spiritual growth. And an encouragement

to seek beauty and creativity in artistic endeavour of any kind.”

De Pulford notes that the iconography schools in Poland are Catholic and will be affiliated with the Ealing Abbey school once it is up and running, resulting in “the joy of its international network”.

The Polish connection is fitting given the words of Pope John Paul II back in 1987 on the 1200th anniversary of the Second Council of Nicaea:

“‘The growing secularisation of society shows that that it is becoming largely estranged from spiritual values, from the mystery of our salvation in Jesus Christ, from the reality of the world to come,” the Pope wrote. “Our most authentic tradition, which we share with our Orthodox brethren, teaches us that the language of beauty placed at the service of faith is capable of reaching people’s hearts and making them know from within the One whom we dare to represent in images, Jesus Christ, Son of God made man, ‘the same yesterday, today and forever’.”

The Pope also appealed to the Bishops of the Church to “maintain

firmly the practice of proposing to the faithful the veneration of

sacred images in the churches” and to “do everything so that more works

of truly ecclesial quality may be produced”.

“These teachings point us to a vision where the Catholic faithful in England and Wales are able, increasingly, to venerate sacred images in their churches which are of a truly ecclesial quality,” de Pulford says.

As with the iconography schools in Poland, the establishment of the Ealing Abbey iconography school represents “a new development in the Catholic Church in this country”, de Pulford says—one that is not linked to dispiriting trends, such as falling church attendance and lack of vocations, rather one that looks forward in hope.

“I am hugely excited about this development in Poland,” de Pulford

says. “If we can achieve a tenth of this dedication and enthusiasm, I

will die a happy woman.”