In the Andalusian city of Seville, annual Holy Week commemorations are a big deal: A major part of the city’s local culture, and an attraction drawing tourists from around the world.

Indeed, Holy Week in Seville is one of the most globally iconic images of Spain.

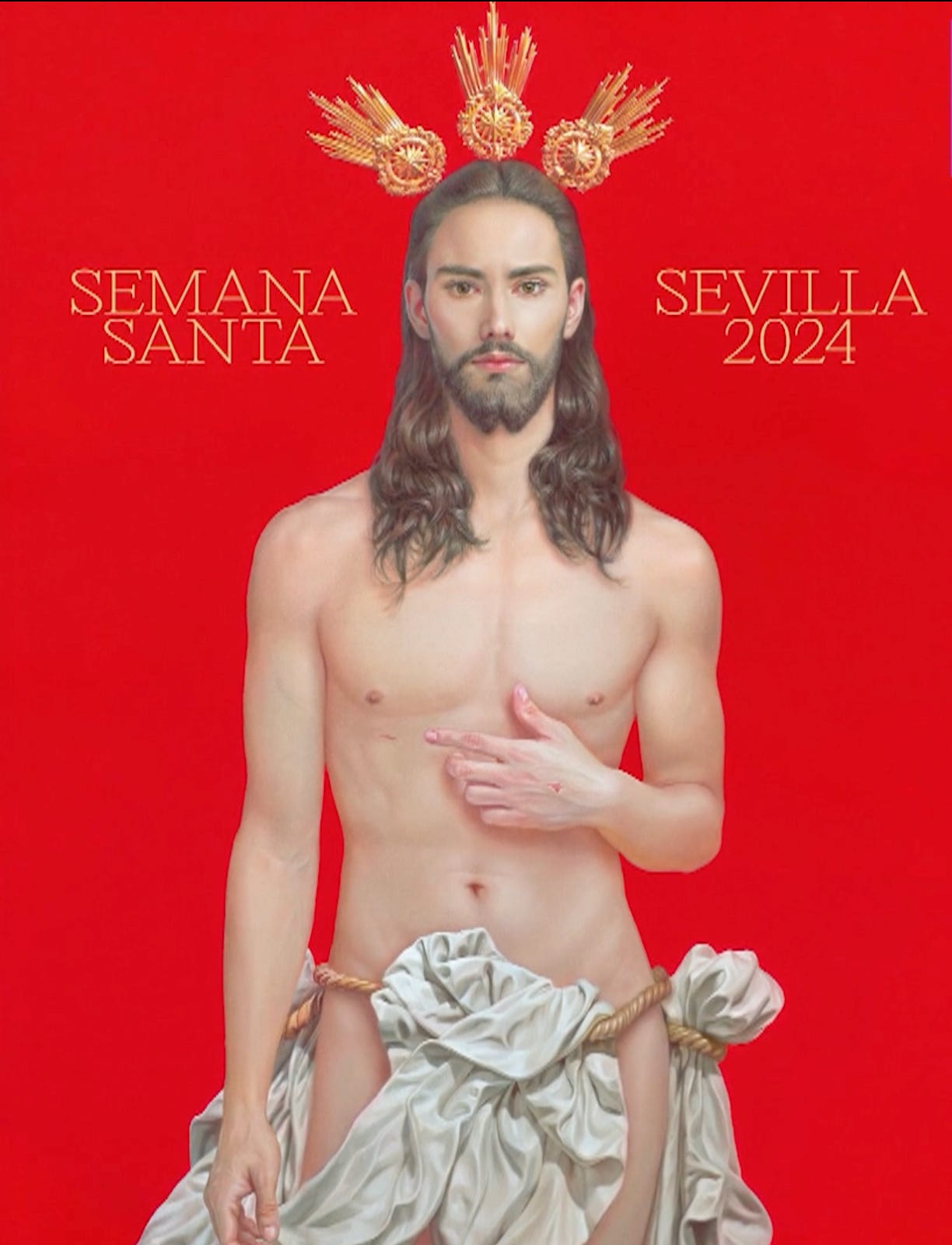

But this year’s celebrations run the risk of being overshadowed by controversy surrounding the event’s commemorative poster.

Holy Week processions and other devotional events in Seville are mostly organized by a commission, the General Council of Brotherhoods and Fraternities of Seville. Each year, that commission invites a famous artist to produce a promotional poster for the city’s commemorations.

But this year’s poster, the work of painter Salustiano Garcia, portrays a hyper-realistic resurrected Christ – modeled on the artist’s own son and inspired by his older brother, who died at a young age – set against a bright red backdrop.

Since it was released last month, the poster has been controversial in Spain.

In Seville, many local Catholics have complained that Salustiano’s Christ is effeminate and too sensual. The controversy has spread among art critics and practicing Catholics, prompting an ongoing debate about the limits of artistic license and its clash with religious sentiment.

A family affair

Outsiders might have a hard time appreciating exactly how important Holy Week is for Seville.

“You can’t understand the city without understanding the importance of Holy Week, how it is lived, and all that implies,” said Gonzalo Barrera, a university professor from Seville who has co-authored a study on the social importance of the festivities, and the Brotherhoods and Fraternities which organize the annual processions.

“These fraternities also do a lot of important charity work during the year, providing medical, financial and social aid, running study halls, and more. They are deeply connected to families, who then participate in the processions,” he told The Pillar.

Another Sevillian, Gonzalo Jiménez, who is active in many of archdiocesan Catholic youth movements, described Holy Week as “a very important part of local culture and tradition. It is moving to see the entire city preparing for the occasion.”

“There is a dimension of spreading the faith to the people, but it is also a great opportunity for people who are more distant to have a personal encounter with God, pray a bit, and return to the family that is the Church,” he told The Pillar.

“For Sevillians, however, there is both a religious and a family component, as we witness one of the most beautiful moments in the life of a believer, the passing on of faith from parents to their children, and from grandparents to their grandchildren”.

The week-long celebrations are not exclusively Church-organized affairs. And they’re theologically complex.

Bernardo Mira Delgado, who has been living in Seville for two decades, told The Pillar that there are aspects of the culture that are difficult for an outsider to understand.

“Spain is a very polarized society, with a very anticlerical left-wing. But it is common to see people who are critical of the Church and of its teachings be very committed to their brotherhood during Holy Week,” he said.

“This mixture of sincere devotion and popular religiosity, mixed with tradition, is something that even now, after 20 years of living in this city, I find difficult to fully comprehend. But since they were born into it, [in Seville] they take it all on board quite naturally.”

Break with tradition

For each brotherhood, the highlight of the week is a procession, in which between 800 and 1,500 members take part.

Each procession includes two heavy platforms, called “andors,” carried on the shoulders of around 40 people.

The first one bears a sculpted image of Jesus, at a certain point of his Passion. The other platform carries an image of his suffering mother, the Virgin Mary.

Each brotherhood processes from its home church to the imposing Cathedral of Seville – a former mosque – and then back.

“Depending on how far away the church is, this can take between four and 14 hours,” Bernardo Mira Delgado explained.

By tradition, the imagery used in the processions and celebrations is somber and heavily baroque.

That traditional approach is why many Sevillians take issue with 2024’s poster, and the painting produced by Salustiano Garcia.

“Personally, I think it is an interesting, modern painting, showing a living and resurrected Christ, but it has absolutely nothing to do with the tradition of Holy Week in Seville. Previous posters tend to capture an image, a detail, which calls for reflection and solemnity. But in this case, the artist just painted his own son, with long hair, and included a couple of details from Holy Week,” said Gonzalo Jimenez.

Barrera agreed: “Personally, I don’t think Salustiano achieved the goal of representing what Holy Week means for this city. Instead, we got a very personal vision.”

“He is clearly a good artist, and if you look through his other works, this is very much his style, but it was not the best proposal for the official poster,” said Barrera. “In the end, it is more a painting of his naked son than of Christ’s passion. It’s not ugly, the picture itself is amazing, but it is too great a rupture with tradition.”

Bernardo Mira Delgado, on the other hand, said that a little rupture might not be a bad thing.

“You need to bear in mind that Seville can be the most traditional and traditionalist city in Spain. Anything that does not conform to ‘the way things have always been’ is criticized. Of course, this has its advantages and disadvantages.”

“My first reaction when I saw the image was of shock, I thought it was an insult to the Church, but now I think it had a positive effect, because society here needs to be rattled every once and a while,” Delgado said.

Still, Delgado remains unconvinced by the image itself. “Not because I find it insulting, but because it does not represent the traditional iconography, nor is it a realistic depiction of Jesus Christ as a real man who lived 2000 years ago.”

“It reminds me of the Passion films of the 70s and 80s, [depicting] a blonde, light-skinned, blue-eyed Christ with three lashes across his back,” he said.

‘Barbie Jesus’

Outside Seville, some art historians and cultural critics have been direct in their criticism of the painting.

Speaking to The Pillar, prominent Catholic art historian Elizabeth Lev, based in Rome, did not mince words when asked about the painting. Lev called it “loathsome” and “tragically, the kind of image I would expect from our sex-obsessed-confused age.”

“He's like PG-13 Barbie Jesus,” she added.

Lev said she found the painting theologically deficient.

“I would add that Easter is supposed to be a great unifying holiday, yet this work is clearly meant to cause division,” said Lev. “So, someone missed the point, that Christ died and was resurrected for us all as sinners.”

“This seems like a pretty small-minded image, like someone asked Chat-GPT to create a Jesus that would cater to an elite few and distress the masses who just want to pray during the Triduum,” she added.

Queer Jesus?

A major criticism leveled at Salustiano’s depiction of Christ is that it is effeminate, or that it was intentionally designed to look “gay,” in order to advance a political or cultural agenda.

Indeed, Brad Miner, senior fellow of the Faith & Reason Institute and the former literary editor of National Review, praised the artist’s “technical proficiency,” but called the image “silly and sacrilegious”, saying the model gives the impression of “a guy ready to march in Seville’s Gay Pride Parade.”

But for Pedro Madureira, a Portuguese art historian who works for a Lisbon-based auction house, there may be a good deal of cultural misunderstanding about how the image has been received outside of Spain.

“I think the painting is very proficient. Yes, some of the details do look effeminate, but if you notice, those are mostly very Spanish traits. He’s not far off from a Flamenco dancer, with his hair caught up on the forehead, and loose around the shoulders,” Madureira told The Pillar.

“What I don’t like about it is his gaze, which is too sensual for a resurrected Christ, and I definitely don’t like the loincloth, which is loose, almost like an open diaper,” he added.

Madureira agreed that the painting breaks with the more static imagery associated with the processions. But he placed it within a particular Spanish artistic tradition of intense realism.

“If you look at the sculptures of Pedro de Mena, for example, they are very pungent. Spanish artists’ treatment of the body is very different from other traditions. Also, from a historical point of view, depicting Christ has always been very tempting for artists as an opportunity to work with the nude body. The same applies to Saint Sebastian,” he said.

“There is no shortage of sensual, ripped, toned Christs. If you look at the images of Christ in the 17th century, for example, they are very toned,” Madureira added, while conceding that “even the Christs from that time look more masculine than this one.”

In Spain, Madureira’s opinion might underscore a split in perception between ordinary Catholics and those who have some sort of training in art or in the history of art, at least according to professor Gonzalo Barrera

“Most people have been very critical, in relation to the style, and what it represents, but feedback has been very good amongst the elites, and art specialists, who understand the meaning of the piece better.” said Barrera.

In that sense, the controversy is nothing new, but fits into a long tradition of creative tension between the world of institutional religion and the world of art, Madureira argued.

“When the Dutch started dissecting bodies and producing very realistic sculptures and paintings, that caused scandal. All the figures on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel were painted nude, until the religious authorities had them covered up, and Bernini’s ‘Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’ was strongly criticized, because it seems to be modeled on a female orgasm, Madureira noted.

“There has always been this difficult dialogue between faith and art. Is that what we are experiencing here? On one hand, my experience as an historian may be blinding me to an agenda the Church should be wary of, but on the other, I sometimes worry that we are so involved in the whole discussion about sexuality that we are reading things into works of art that the artists themselves did not intend.”

In Spain, a big part of the debate is between commentators who say that criticism is “homophobic,” and other Catholics, who say they believe the poster does represent a cultural or political agenda, or that the painting is clearly intended as a provocation.

But for his part, Gonzalo Jimenez said that “some sectors label as homophobic anyone who thinks that an effeminate image of Jesus Christ is inappropriate,” adding that “many homosexual members of the brotherhoods have come out publicly saying that they are also against the poster, and that it has nothing to do with homophobia, but simply with the fact that it goes against tradition.”

Gazing on the crucified Christ

Whether or not there is an agenda, ecclesiastical officials in Spain have decided not to comment on the matter publicly — though the bishops could rightly point out that they did not commission the work in the first place.

The General Council of Brotherhoods, on the other hand, has also chosen not to speak out, according to Spanish press, despite fierce internal criticism from some members, in order to avoid giving the matter even more publicity.

Nevertheless, discomfort with the issue is evident.

The day after controversy broke out in Seville and started going national, Seville’s Archbishop, José Ángel Saiz Meneses, did publish a post on twitter.com that has been interpreted both as an indirect criticism of the painting and as a call for Catholics not to be distracted by the controversy from Holy Week itself.

Above a very traditional image of the Crucified Christ, the archbishop placed a quote from Pope Benedict XVI, beginning with the words “let us gaze on the crucified Jesus.”

The president of the General Council of Brotherhoods and Fraternities repeated those same words when asked to comment, after saying that he would not be airing the organization’s internal discussions on the matter.

Meanwhile, as Lent draws closer, the several thousand people who have signed a petition asking for the poster’s removal seem less and less likely to see their goal achieved.

For many local residents, however, there is no doubt as to where the responsibility lies. “I don’t think we can blame the artist, and I don’t think he was trying to provoke. This painting is clearly within his style,” Gonzalo Jimenez. “We need to look further up, to whoever commissioned it, and ask why they chose him in the first place.”

‘Neither revolutionary nor dirty.’ Heretical?

The artist, Salustiano, has defended his painting, and seemed genuinely surprised by the controversy, describing it as “neither revolutionary nor dirty.”

In a recent press conference he told reporters that “I wanted to focus on the most radiant part of Christ, His resurrection. And I wanted to be faithful to my own style, which is to work with people, with living beings, and not just copy images.”

“I meant to paint a young, beautiful Christ, no longer bearing the marks of torture, because I wanted to represent the God that is in Christ, since He had left the human part of himself on earth, and is now ready to be 100% God,” he added, apparently unaware that his statement could be considered to constitute heresy, since Christianity holds that Christ is both entirely human and entirely divine, and that he resurrected bodily and ascended physically, not merely as a God who left his humanity behind.

“Some have said that the painting is revolutionary, but it is not, because I didn’t want it to be. I wanted to produce a nice and respectful painting for the entity that commissioned it, and for all Christians. I never meant to offend anybody, and indeed, the references in the painting are from my own family, including my older brother, who died young, and my son, who was the model. I treated both with love and absolute respect”, Salustiano added, putting negative opinions of his work down to “lack of culture and ignorance.”

His critics, he said, “must have never been to a museum, or even a church, because I didn’t make up a single one of the elements in the painting”, the artist stressed.

“We are in 2024. I am faithful to tradition, and I am faithful to the religion I was born and raised in. And all of that is in the painting.” he concluded.